(SALT LAKE CITY)—Using X-rays and neutron beams, a team of researchers from the University of Utah, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Oak Ridge National Laboratory have revealed the inner workings of a master switch that regulates basic cellular functions, but that also, when mutated, contributes to cancer, cardiovascular disease and other deadly disorders.

Learning more about how the Protein Kinase A (PKA) switch works will help researchers to understand cellular function and disease, according to Donald K. Blumenthal, Ph.D., associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Utah (U of U) College of Pharmacy who led the study. “To develop new drugs and treatments for disease, it’s important to understand how PKA works,” he says. “This study helps us get a clearer picture of how the PKA protein helps regulate cellular function and disease.”

The study, published in the Oct. 10 issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry as its paper of the week, features research conducted using the Bio-SANS instrument at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR), a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

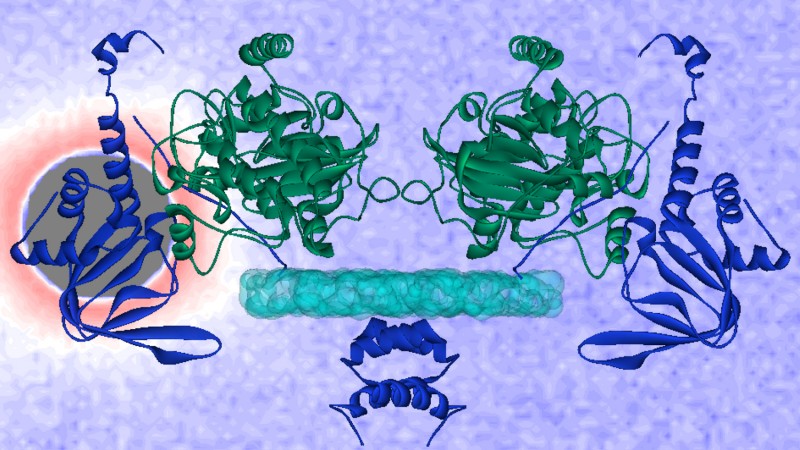

The PKA protein comes in four forms, each of which serves as a sensor for a signaling molecule called cyclic AMP (cAMP). When these forms of PKA sense cAMP, they change shape, which researchers believe is critical in determining how PKA works as a biochemical switch. Many hormones, neurotransmitters and drugs communicate with cells by changing the level of cAMP found within them. Accordingly, PKA helps regulate cellular activity in reaction to different levels of cAMP within cells. Because PKA serves as a master switch in cells, mutations in it lead to a variety of diseases including metabolic disorders, disorders of the brain and nervous system, cancer and cardiovascular ills.

Blumenthal and colleagues focused on a form of PKA called II-beta (two-beta), a protein found mostly in the brain and fat cells that is suspected of being involved in obesity and diet-induced insulin-resistance associated with type 2 diabetes. II-beta contains two structures for sensing cAMP, each of which cause II-beta to change its shape in response to the signaling molecule.

The researchers wanted to know whether both of II-beta’s cAMP-sensing structures are required to determine its ability to change shape – a critical factor for its function. To answer this, they removed one of the cAMP sensors and used small-angle neutron scattering at HFIR, and small-angle X-ray scattering at U of U, each of which reveals information about the shape and size of molecules. The results of the study showed that II-beta does, indeed, change shape with only one sensor.

“By process of elimination, this must mean that parts of the remaining single sensor of II-beta give it its unique shape and internal architecture,” says Susan Taylor, Ph.D., professor of chemistry, biochemistry and pharmacology at the University of California, San Diego, and co-author on the study. “Our findings further narrow and define the key components of II-beta and identify new regions for further study.”

Future research should focus on a part of II-beta called the “linker region,” which connects the remaining cAMP sensor with a part of II-beta that helps target PKA to specific cell locations, according to Blumenthal. “Based on what we know about II-beta and other forms of PKA, it’s likely that the linker region plays a major role in organizing the internal architecture and shape changes determine the unique biological functions of each form of PKA.”

The study’s co-authors include Jeffrey Copps, Eric V. Smith-Nguyen and Ping Zhang, UCSD Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and Howard Hughes Medical Institute and William T. Heller, Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Funding support for this research came from the National Institutes of Health (grant GM34921). The Center for Structural Molecular Biology operates Bio-SANS, the HFIR instrument used for the neutron scattering experiments, and is supported by the DOE Office of Science, which also supports HFIR.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for the Department of Energy's Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov/.

- Katie Bethea, 865.576.8039