Neutron scientists are partnering with industry to enhance engine and commercial cooling technologies in hopes of making improvements that will optimize fuel and energy efficiency.

Hassina Bilheux, a physicist and the lead for developing ORNL’s neutron imaging capabilities, uses cold neutrons at HFIR's CG-1D beam line to image automobile engine system components, two-phase fluid components in commercial cooling systems, and electrodes used for lithium batteries.

Neutron imaging is just taking off at ORNL, and although there aren't yet any instruments devoted exclusively to it, Bilheux and her colleagues have been using one of the cold neutron beam lines at HFIR for imaging work. “These are not imaging beam lines,” says Bilheux. “But we have been very successful since we started in December 2009 preparing CG-1D for imaging.”

Bilheux hopes to eventually bring neutron imaging capabilities to SNS, where she can better and more cost-efficiently select the energy of the neutrons. SNS, she says, has a wide range of energies that makes it possible to image thick biological samples, which isn't possible at HFIR.

Progress is visible now in a series of industrial research projects already afoot or in the planning stage. Two of the projects under way involve vehicle technologies: producing two- and three-dimensional images of exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) coolers and images of diesel particulate filters (DPFs), which remove the black soot cloud so often associated with diesel exhaust. In both cases, the goal is to improve fuel efficiency and, in the case of the DPF project, to consider the emissions and materials impacts of the introduction of biofuels.

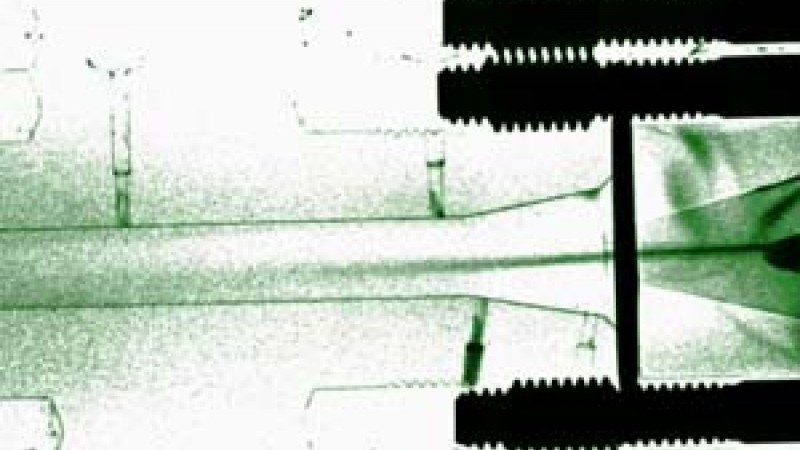

To take measurements, researchers set a sample in the beam and use a detector behind it to collect the neutrons that are transmitted, literally taking shadow pictures of the sample. “Neutrons are especially great for engineering applications because they don’t see metals very well but are efficient at seeing hydrogen-rich fluids,” Bilheux explains. In the EGR coolers project, researchers measured coolers from 10 participating companies.

Neutron imaging measures how the hydrocarbon (enriched particulate matter) is deposited within an EGR cooler that shows significant clogging. The role of the coolers is to lower the oxygen content and the combustion temperatures, thereby reducing the formation of NOx (nitrogen oxides) in the cylinder. Thanks to the imaging, the researchers can measure the thickness and hydrocarbon content of the deposit and come to understand the spatial and time dynamics of particulate matter deposition. In future measurements, tomography will be used to image complete, intact coolers in three dimensions.

A second vehicle project concerns how soot and ash build up in the DPF of a diesel–powered vehicle and the impact of fuel type. DPFs were developed to remove the particulates (primarily soot) once common in diesel engine exhaust. Bilheux is working with researchers at the Fuels, Engines, and Emissions Research Center (FEERC) at ORNL’s National Transportation Research Center. At FEERC, the researchers use diesel engines operated on dynamometer platforms to introduce particulates to the DPF. This enables the study to occur on real engines under industry-relevant conditions; additionally, field-aged samples have been provided to the FEERC researchers from industrial partners.

The work began with measurements of DPFs at different soot and ash loadings. As the neutrons are able to penetrate the ceramic filter, they can take measurements of the hydrocarbon-rich particulates (soot) and metal-oxide–based ash. Although these materials are not necessarily highly sensitive to neutrons, they have a high surface area and are very hydroscopic (readily attracting moisture). The adsorbed water allows detection by neutrons. Neutron tomography is used to view and measure the thickness of the soot in the channels and the location of ash deposits. Ash, mostly from lubricant additives, affects engine efficiency by clogging the filter and increasing the backpressure on the engine and curtails filter life.

Bilheux is also engaged with computational scientist Sreekanth Pannala and battery expert Jagjit Nanda at ORNL, as well as industry partners, to measure lithium transport inside complex electrodes.

“This is an important research area for DOE and involves substantial participation by industrial partners,” Bilheux says. Battery storage devices have excellent energy and power-to-weight ratios and are now the power source of choice for cell phones, cameras, and notebook computers. Lithium batteries are also used extensively in biomedical and military applications, and prospects are good for the use of lithium batteries in transportation in the future.

Bilheux is also working on multi-constrained jet flow with the United Technologies Research Center. Neutron imaging is being used to examine jet flow under different conditions to investigate new design capabilities for multiphase ejectors that can improve heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning system efficiency. There are currently no data on internal ejector flow to validate physical models needed to improve ejector design. Neutron imaging can provide these data.

Says Bilheux, “SNS and HFIR, to me are like a train, and it is on a fast pace, and you just jump on it and go with the flow!”

Research at HFIR was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Basic Energy Sciences.